Seven years ago today, Kirsten called with news that changed our lives forever. I still have the text exchange on my phone from July 26, 2015. She was away at college, very sick with what she thought was the flu, and a caring friend was driving her around trying to find an urgent care facility that would see her (i.e. accept her insurance). The situation was getting desperate when she texted me for help. As I frantically searched for a location in her area online, another text came through…

“Did you figure it out yet? I am f*king dying here.”

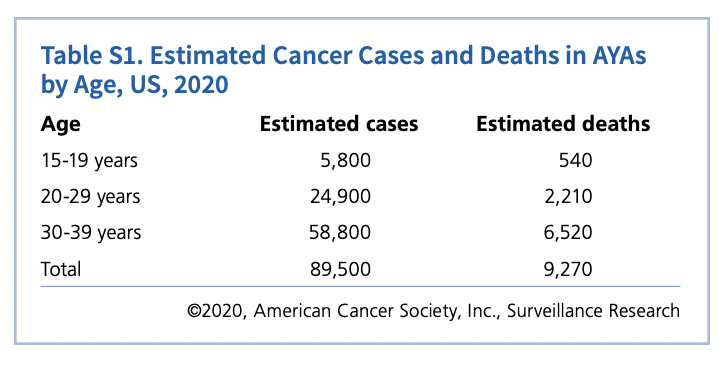

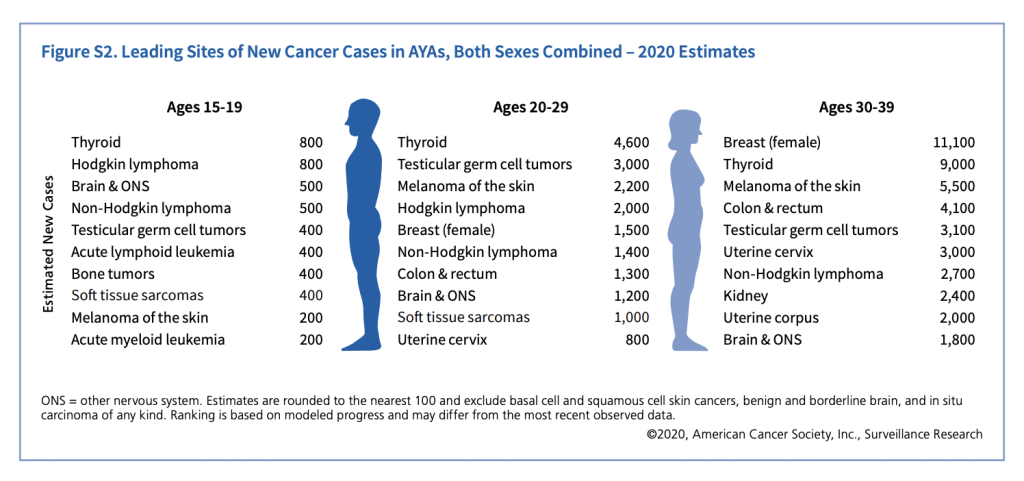

Ugh. Little did we realize. After giving up and telling her to go to the emergency room, I would wait anxiously for two hours before we would hear from her again. That call is the one that will bring parents to their knees. “The doctor says I have leukemia, and he is trying to find a hospital that has beds available. He said I need to go right away.”

From Kirsten’s diagnosis to the tragic loss, life was disorienting, chaotic, emotional, and exhausting. We felt like we were constantly climbing the cancer learning curve, with so many lessons learned along the way. What I would have given for my future self to offer a few helpful tips before stepping into Kirsten’s hospital room for the first time later that night.

Over time, we all become experts of our own unique experience with cancer, so my hindsight may have its limits. But in memory and in honor of Kirsten’s experience and the challenges we experienced navigating the ups and downs as parents of a young adult with cancer, I offer the following advice to other parents who have recently been informed their (young adult) child has cancer.

Parents, find a balance between giving care and giving space

As a parent, when your child is very ill, no matter what age, it is natural to want to do everything you can to protect them. But for a young adult, that can sometimes feel smothering. Have the awareness and take the time to ask them how they want to be supported. Recognize when your care is helpful and when it might feel like too much.

I often felt like I needed to be in the room with Kirsten in case something bad happened. But bad things may happen whether you are there or not, so for your mental health and theirs, find time to take for yourselves (and give them alone time). When you are in the room with them, they may not be able to truly act and feel like themselves.

If they were an independent young adult before the diagnosis, it can be very frustrating to lose that sense of freedom and control. Yes, they will need your help. But give them control where you can, even if it is just giving them a choice about what they want to eat, when they want some alone time, or who they want to visit (or not), etc. When Kirsten’s friends came to visit, we stepped away but let her know we were a text away if needed.

Parents, do what you can to mitigate physical and emotional isolation.

One thing that has become very clear over the last seven years, the health risks from isolation can have lasting effects. Look for the signs, and work with the psychosocial team to mitigate the impact where possible. Isolation is more than just being alone in a room. It can be felt when they can’t express how they are feeling, when they are unable to do normal activities, and when they don’t have access to peers with shared experiences. And when we apply labels like “you are strong” or “you are an inspiration,” they feel they have to live up to the label, preventing them from sharing how they are really feeling.

By providing a safe space for young adults to share their emotions – name them, understand them, and process them – they can cope and move forward. So when they are sharing how they feel, try not to change the subject, attempt to fix it, or be dismissive. All of those responses invalidate their feelings. Also, there are some topics they need to talk about, but you or other members of the support team might not be the right audience. Depending on the topic, other peers, a trained health professional, or therapist is needed. The best help you can offer in those situations is to ask how they need to be supported and then help them find those other resources.

A word of caution, hospital privacy rules can be a major impediment to meeting others going through a shared experience. Often they are just down the hall, but you will never know. Remember, YOU have control over your own privacy wishes – the best way to meet others may be to give the hospital staff permission to let others know you are there and want to meet. Provide it in writing if needed. Kirsten would do the same thing to seek out other patients. As a consenting adult, she would provide her cell phone number and give the doctors and nurses permission to share it with anyone her age who wanted to meet in the hospital. The rest was up to the recipients to follow through. Your mental health depends on connection and having outlets and people to talk things through, so find ways to make it happen.

Parents, respect their boundaries and right to private conversations with their medical team.

Let them be the ones in control of the speed and direction of information flow with the health professionals. Their body, life, and future are at stake – give them the opportunity to have full access to the information that affects their future – they should feel comfortable speaking freely, asking questions, answering honestly, and being involved in the decision-making process. Also, respect their privacy boundaries – and try to have the awareness to know when conversations head in that direction and offer to step out without being asked.

And this can’t be emphasized strongly enough…if it gets to the point where they ask you to step out of the room, do it without making them feel bad. It takes courage to speak up, and they need to feel safe making that request. Remember, it is not personal, and it’s not about you. Private topics can include family planning and fertility preservation, sexual activity, and lifestyle choices. For some topics, like fertility, they may not have thought about it until this moment, but they deserve to know how their treatment will impact their future ability to have a family.

There is nothing worse than feeling like, “why didn’t anyone tell me?!” after treatment is over (or it’s too late to take action). Kirsten was very engaged and curious about her condition, treatment, and how it impacted her future. Due to the severity of her cancer, she did not have the time to consider fertility preservation. Still, the information provided by the medical and psychosocial team helped her gain control over one of her biggest fears – fear of the unknown.

Parents, don’t assume you know what they need, be sure to ask.

As an independent young adult, the last thing they want to feel is dependent on their parents again, but they will need and want your support. Just make sure the support you offer is the support they want. Physical and emotional needs will change as treatment and other factors change. Be mindful and present in the moment when you are with them. It will help you tune in to pick up on the spoken and unspoken cues. That means leaving work, other family stress, financial concerns, etc., outside the room when you can.

But even when you are “dialed in” after spending months together, you will still get it wrong. It’s inevitable. But by taking the time to ask the simple but important question, “How can I support you today?” you are allowing them to regain control over what they can control, and in the process, you are getting them what they need. They may not always have an answer (which is okay too), but at least you extended the courtesy of asking.

Parents, where possible, preserve normalcy, including activities, family time, and routines.

When a diagnosis happens, it’s all hands on deck to save a life, and all focus shifts to the person with cancer. It’s a marathon, not a sprint, and that long-term focused attention can create collateral damage to other family members and relationships. As soon as possible, check in as a family and establish some important ground rules to keep the lines of communication open, find routines that you can sustain, and identify activities that are important to maintain.

Siblings are often asked to take on extra chores, help with school, and sometimes even pick up a job to help with finances. They may sacrifice activities with friends or school milestones because they feel the need to always be strong and mindful of their sibling with cancer. Unfortunately, jealousy, resentment, frustration, and isolation can build up over time, and they will feel isolated, and their mental health will suffer. Give them breaks, have one-on-one time with them to talk and allow them to do special activities. Make sure they still get to live life and have time to enjoy friends.

And for spouses or life partners, make time for each other as well. Plan your own private time away from the hospital together to talk and reconnect. Remember, your child will also want their quiet time, so this is a great opportunity for everyone’s self-care and mental health.

Parents, watch for signs of financial stress and guilt.

The physical and emotional toll of cancer is bad enough, but the financial damage caused by cancer is also devastating and often hard to recover from. Cancer treatment and all of the secondary costs, including lodging, food, and alternate care for family, can add up FAST. When Kirsten was first diagnosed, we had no idea what to expect, and that one-week hotel reservation turned into a three-month extended stay – and it was out of network for health insurance. And since Kirsten was an adult being treated in the children’s hospital, none of us had access to any available services that would have helped offset those costs.

In the three months we were displaced, we would burn through nearly $40K of non-reimbursable expenses – just for lodging! That doesn’t even scratch the surface of the bills I saw go back and forth between the hospital and the insurance company. Without insurance, everything we had saved for the last 30 years would have been gone by the time treatment was over. My husband was between jobs, and we had no idea what would be approved or denied during treatment. Only after Kirsten was transferred back to San Diego would we become aware of just how stressed she was about the cost of her treatment and her concern for how it impacted all of our futures. That is a heavyweight for a young adult with cancer to bear on top of everything else.

Parents, asking for and accepting/declining support is stressful, but it doesn’t have to be.

Support stresses everyone out at some level. Those in your circle who want to support worry about calling at a bad time, offering the wrong thing, or making things worse, not better. Remember, people want to help, and sometimes all they need are clear directions. And when you are the one in need of support, there is the stress of being a burden, seeming needy, weak, or incapable of caring for your own family, or on the flip side, not being in the mood for the support that is being offered and feeling guilty declining.

So much energy is wasted on the stress of communicating needs and offers of support. I regret not accepting the offers from friends and family. It would have given us welcome relief and the support system the joy of feeling helpful, making a difference, and providing comfort when someone needed them.

Reducing this stress is easier said than done, but one possible tactic is to make a list of all the things preventing you from being present for a loved one that you find yourself thinking about but don’t have the time to do. Post that list (or have it ready to share when people call or text) and let your network pick and choose what they feel comfortable helping with.

When you decline offers for support, provide constructive feedback that allows the support network to make helpful improvements for next time. Things like exhaustion, diet restrictions, changes to smell or taste, and other sensitivities are all perfectly acceptable reasons for declining or requesting an alternative. “Thank you for the offer. I’m not feeling well today. Can we reschedule for another time?” or “I appreciate the offer to bring ___, but a better alternative would be ___.” Honest and thoughtful guidance will make it better for you and them next time.

Parents, find a method of communication that works for you and them.

The tools you need to communicate with family may be very different from those you need to communicate with their young adult friends. Find the tools and resources that make life easier, not harder, to keep everyone updated and engaged. There are lots of resources out there. Ask the care team and other caregivers and patients to find out what they use.

Respect privacy, and make it clear to others what they can or can not share. You don’t have to personalize every email – people understand and appreciate any updates. It also opens the door for them to reply when they might otherwise avoid connecting for fear of disturbing you. Also, consider how your updates will affect young adults reading it for the first time. For many, the news, and even the updates, can feel very scary, and have them worrying about death and even questioning their own mortality.

It is okay not to provide updates until you have more information. Avoid throwing the word cancer out there and then going radio silent for days. Only share information with people that you know and trust. And don’t be afraid to remove or block people that feel toxic or are less than helpful. Information sharing is first and foremost to help people provide support and comfort. If they create more work and stress for you than comfort, it is okay to take a break from connecting with them.

Parents, be patient, be kind, and find forgiveness.

Being in close proximity for extended periods, mixed with fear, uncertainty, loss of independence, and friendships combine to turn life into a giant pressure cooker. The stress is enough to end relationships, break up marriages, create long-term resentment amongst siblings and parents, and unfortunately, contributes to all kinds of physical and emotional baggage down the road. It will be hard work to keep it together sometimes, but for everyone’s sake, do your best to act with kindness and when that fails, gather the courage to ask for and find forgiveness.

When feelings start to escalate, breathe. Have the self-control to take a break and walk away (but don’t storm away). It doesn’t do any good to argue and negatively impacts their health and yours. The closer we are, the more comfortable we are to vent and even say hurtful things. Hold the space for each other to express those feelings and try not to take them personally. Mistakes will be made but do your best. That is all anyone can ask

Keep your head up. Take care of yourself and each other. There will be good days and bad days, but every day you get to spend with each other is a gift. Many things about cancer are out of your control. So don’t waste time worrying about those. What you do have control over is how you choose to live each day and how you choose to treat each other. Do your best to make every day a little better.

Want more?